Results Roundup: New Findings from First-Time Parent Programs

At a recent First-Time Parents webinar, hosted by the Evidence to Action (E2A) Project, Georgetown University Institute for Reproductive Health, and Pathfinder International, we invited Oluwayemisi Femi-Pius, Akim Assani Osseni, and Bryan Shaw to share their insights on results from recent projects targeting this critical and underserved youth population in Nigeria, Niger, and DRC. See below for their full presentations, and read on for an additional Q&A.

Q&A

Program Implementation

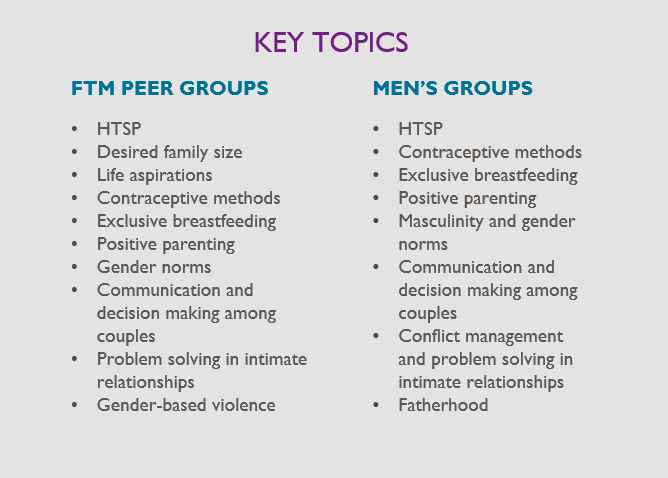

In Nigeria, how did you decide which topics would be covered with FTMs and their partners?

Oluwayemisi Femi-Pius, MD, Senior Technical Manager, Pathfinder International Nigeria: Prior to the project, we conducted a formative assessment that helped us understand some of the priority needs and concerns that FTPs faced during the postpartum period (which was the focus for our project). From this, we identified key topics to incorporate in the program, making sure the same topics were addressed for both the FTMs and with their partners. Where possible, we leveraged existing, tested curricula and tools—especially activity cards developed by the GREAT project.

In Niger, how did the project address polygamy and norms that provide protection from rapid repeat pregnancy?

Akim Assani Osseni, MPH, Reaching Married Adolescents Project Technical Manager and Acting Community-Based Service Manager, Pathfinder International Niger: By involving co-wives and mothers-in-law in the implementation through sensitization, we not only succeeded in breaking the idea of competition in the number of children between married adolescents girls and their co-wives, we also succeeded in strengthening family ties, thus creating a favorable environment for married adolescents girls. Also, since Niger is a predominantly Muslim country and Islam allows polygamy, our project brought in and trained religious leaders.

In Nigeria, how did the program differ for single mothers or parents that were not cohabitating or in a relationship?

Dr. Femi-Pius: This is a really important issue and one that we grappled with. When we started the project, we were not sure who would participate. Through the formative assessment, we had learned that partner relationships were often very fluid at this time, so it was difficult to predict and design for specific subsets of FTMs. We offered the same peer groups intervention to all FTMs, and for those who had a partner that they wanted to involve in the program, we were able to engage him as well. We also reached older women, who are often very influential—especially with unmarried FTMs. Overall, we saw strong results for both married and single FTMs, which suggests that the program addressed at least some of their needs/concerns. But programming specifically for different types of FTMs is absolutely something to consider.

Did your program in Niger address any issues related to early marriage, given the contact with community leaders and influencers?

Mr. Osseni: The program was not designed to address the issues of early marriage, which are still sensitive in our rural context. However, certain aspects, such as the right to schooling for children (especially young girls) and responsible parenthood, were addressed with the support of religious leaders. The program is designed to prevent the consequences of early marriage by preventing early pregnancies (before the age of 18), by monitoring pregnancies among married adolescents girls on a quarterly basis, by facilitating delivery in a health centre and by following up on the child until full vaccination is achieved; obviously with the use of family planning.

Have any of your projects in Nigeria and Niger been able to integrate non-health issues into programs for FTPs—especially in terms of economic opportunities or education?

Dr. Femi-Pius: In Nigeria, we absolutely saw the need to do this and made efforts to link the first-time mothers, through our partner community-based organization, to government-proposed educational and economic empowerment initiatives. Unfortunately, these had not started by the time of our FTP project, but the CBO is there to help make connections as these government programs evolve.

Mr. Osseni: In Niger, to strengthen the autonomy and employability of adolescent girls, during the last year of the project, we integrated income-generating activities for young mothers who had completed the entire project intervention package. The activities were seen as extremely beneficial to the young mothers who participated, including perceived increases in financial autonomy and cohesion among the participating women. The perceptions of the husbands were more mixed, which is informing how we plan, implement, and evaluate such programs going forward.

How do the costs per young woman reached compare across the different program models? Has there been any (difference in difference) analysis comparing interventions that involved just one or two levels of the socio-ecological model vs. all the levels? Also, four months versus two years must represent very different costs.

Mr. Osseni: Unfortunately, we have not evaluated the costs of the different approaches to FTP interventions through this project. But from the experience of another Pathfinder project—our Reaching Married Adolescents project (RMA), also in Niger—which evaluated the costs of the different approaches, we do know the following about costs:

- After approximately 1 year of RMA implementation (midline survey), home visits were the most cost-effective approach when looking at cost per new FP user

- Combined approach (home visit and small groups discussion) was slightly more expensive (1.17x) compared to home visit approach

- Small groups discussion approach was twice as expensive (2.21x) compared to home visit approach

- After approximately two years of RMA implementation (endline survey), regardless of whether the various approaches continued receiving RMA support after midline, all three approaches had similar cost per new FP user, EXCEPT…

- Participants in the small group that received RMA support for the first year, but received no additional RMA support in the second year, were found to be the most cost-effective approach at endline

Both Pathfinder’s FTP and Reaching Married Adolescents (RMA) interventions targeted all levels of the socio-ecological model. While RMA looked at the efficiency of the home visit and small group discussion approaches and the combination of both (home visit and small group discussion) in recruiting new FP users and changing social norms limiting access to FP by adolescent girls, the FTP program relied, instead, on the combined approach to reach its target at all levels of the socio-ecological model. Thus, none of the RMA or FTP interventions will allow for a comparison of the involvement of one or two levels of the socio-ecological model versus the involvement of all levels.

Can you please shed more light on your strategies to increase service utilization / generate demand?

Bryan Shaw, PhD, Senior Research Manager at the Georgetown University Institute for Reproductive Health: Our activities in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) are directed toward improving attitudes and social norms toward use of FP. We hypothesized that this will lead to increased demand (and it did). Service linkage activities were also taking place to ensure youth-friendly access and information to FP services.

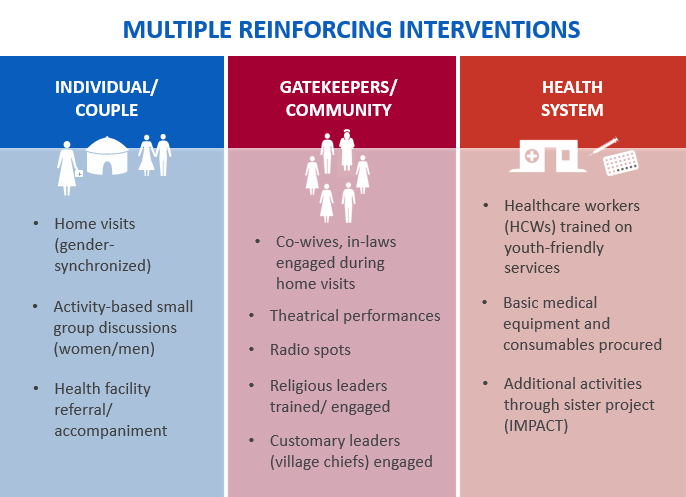

Mr. Osseni: In Niger, we generated demand by sensitizing our targets at all levels of the socio-ecological model and by using all the channels provided by the project:

- Home visits to married adolescents girls by the female and to husbands by the male

- Small groups discussion of men facilitated by male Relais and women facilitated by female Relais

- Theatres forum addressing key themes on RH/FP and targeting members of the community

- Broadcasting of radio spots also addressing key RH/FP themes and discussion of the episodes in women’s and men’s listening clubs.

- Preaching conferences by religious leaders, etc.

Dr. Femi-Pius: In Nigeria, we also integrated demand generation (for FP and other health services) across all activities with FTPs, and engagements with CVs helped to create linkages to nearby facilities. Key interventions that addressed demand generation included:

- FTM Peer Groups

- Male Partner groups

- Home visits by Community Volunteers to provide tailored counselling and referrals

- Activities with older women influencers and community members to build support for FTP health service access

- Mobile outreaches by health facilities

How were the trained health care providers’ contribution particular to FTPs in Niger?

Mr. Osseni: Married adolescent girls do not have the same health service needs as adult women with more reproductive health/family planning experiences. The project’s community workers created demand for RH/FP through outreach. To ensure the supply of RH/FP services that meet this demand, service providers in the 16 health centers affiliated with the project were trained on the supply of adolescent-friendly RH/FP services. This helped to establish a positive rapport between married adolescent girls and health providers, facilitating antenatal care, assisted delivery, postnatal and infant consultation visits.

During the selection of the community volunteers in Nigeria, did you consider age? Did you take peer-to-peer influence into consideration? And were they paid?

Dr. Femi-Pius: Yes, we did consider age, but in some communities, the only available CVs (unemployed CHEWs) were older. They were given a monthly stipend of approximately US$55 through our CBO partner. We did consider the importance of peer influence and this was a cornerstone of our project. At the outset, we worked with community leaders, health providers and our CBO partner to identify and train young FTMs to act as ‘peer leaders.’ These young women helped to identify other FTMs through their networks and led all 14 sessions of the FTM small group intervention.

Gender

Were there any challenges in engaging male partners in the Niger project activities?

Mr. Osseni: Migration, particularly of the husbands, has been a major challenge, particularly for a project that takes a gender-synchronized approach. We need to better account for seasonal migration of men; the project tried to condense visits/shift them to evenings, but we want to explore how else to more consistently reach these men.

Do you have any results for the men who participated in the Niger FP project?

Mr. Osseni: Our study measured improvements in gender equity-related attitudes among participating husbands, including:

- significant increases in the portion of husbands who consulted their wives about birth spacing (67% to 98%) and

- significant decreases in husbands who thought that women alone are responsible for domestic tasks (97% to 46%).

We also saw an increase in the number of men who responded affirmatively to the question of whether women should tolerate intimate partner violence to maintain the status of their households—from 3% at baseline to 53% at endline. We’ve been exploring whether this is an unintended consequence of delivering norm-changing interventions, which included income-generating activities with the wives (backlash to gender-norm transforming interventions is well-documented in this field). Pathfinder has also been exploring what programmatic and technical approaches can be used to combat these effects going forward.

In addition, from focus group discussions with relais communtaire (community health workers), we learned there was a perceived increase in involvement of husbands in choosing contraceptive methods as well as contributing more to housework.

Do other data from the DRC project—especially qualitative findings—share any insights into the intimate partner violence (IPV) issues faced by first-time parents (FTPs)? Are there specific factors that contribute to IPV during this lifestage? And any lessons learned on IPV interventions that might work well for FTPs?

Dr. Shaw: From our qualitative work, we have some indication that first-time parenthood is a highly stressful period, especially for women. There were mentions of heightened economic anxiety about expenses associated with a child. We also note that among scenarios for IPV being justified, the majority of respondents noted that IPV was justified for a “wife that neglected her children.” There was considerably higher support for this justification compared to other things (e.g. going out without telling a husband).

Call you tell us more about how gender equality or gender transformative approaches can address FTPs, especially delaying first birth?

Mr. Osseni: In Niger, the project was implemented using a gender-synchronized approach. Sensitization of both the married adolescent girl (under 18 years old) and her husband in favor of FP to delay the first pregnancy by different project actors and through different channels (home visits, small group discussions, forum theaters, preaching conferences, radio spots, etc.) was instrumental in the process.

Dr. Shaw: In the DRC, the project was implemented using a gender-transformative approach. In addition to activities targeting norms around IPV and FP, norms relating to gender equity and household roles (childcare and household chores) were targeted. This included critical reflection on these norms in couple dialogues (guided by a gender champion), couple testimonials, and supportive sermons (with positive scriptural messaging).

Dr. Femi-Pius: In Nigeria, our project was designed to work with FTPs after the birth of their child, so we were not able to address this. However, our project did use a gender-synchronized approach to address norms around household roles and decision-making, and examine key couple dynamics such as communication, conflict management, and parenting. We saw significant improvements in a range of gender attitudes and our key outcome of interest—FP use—for both FTMs and their partners.

Religious Influences

I’m interested to hear more about how religious and traditional leaders were engaged in the program in Zinder. What is the evidence that their involvement in the program helped combat unhealthy rumors?

Mr. Osseni: We have developed a religious justification that lists and explains all the Quranic verses and hadiths supporting FP. Then, in each village, two religious leaders were trained on this leaflet, which enabled them to hold quarterly preaching conferences in their villages. This reinforced the intervention’s messages, allowing the beneficiaries to believe in FP and combat unhealthy rumors. This resulted in a decrease in reluctance and an increase in the use of FP/RH services by married adolescent girls.

We have also established a close relationship among community agents, religious leaders, and traditional chiefs—so that the latter are fully informed about project activities in their villages.

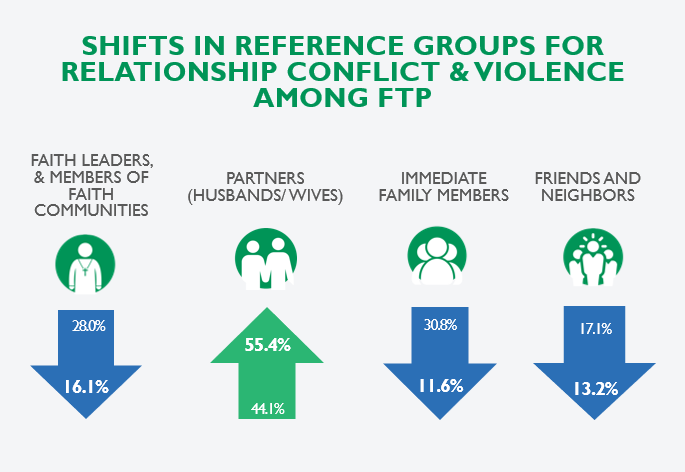

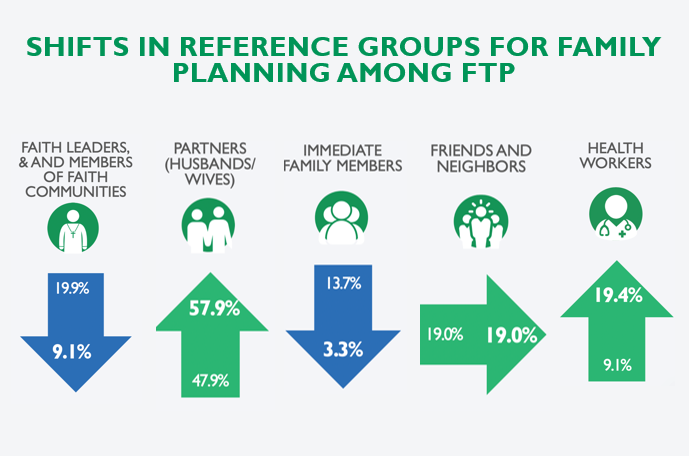

I am worried about religious backlash to Western interventions in the countries where most of our work happens. I am wondering if the religious leaders’ influence decreased in comparison to others’ influence increasing or if their absolute influence reduced in these subjects. Also, were any of their reactions to these findings explored? If so, how did they feel about having less of an influence?

Dr. Shaw: We saw decreases in relative and absolute influence of religious leaders specifically for norms related to FP and IPV (and increases in HWs and partners). This endline occurred during a period of instability and decreased church attendance, so it is hard to say with certainty whether this is an artifact of the intervention or of circumstance. Given we saw similar reductions in the comparison congregations, we think it was the latter. We are following up this work with qualitative work where this will be one of the main explorations.

Mr. Osseni: In Niger, religious leaders always have a great influence in the implementation of FP/RH interventions. Most of the time, they play a very positive role in this influence when they are involved in the implementation. Negative influences often come from ignorance. For example, during the training of religious leaders on FP religious arguments, many of them were unaware of the existence and meaning of the Koranic verses and hadiths supporting FP. Unfortunately, we did not explore their reaction to the results of the final survey of the project.

Contraceptive Uptake

What FP methods did FTPs and newlywed couples prefer?

Dr. Shaw: In the DRC, among the 39.9% of the sample that are current users of modern contraception, FTP at endline reported that they were currently using: male condoms (48.8%), OC (21.4%), FAM (16.3%), implants (12.1%), injectables (6.1%), and IUD (1.0%).

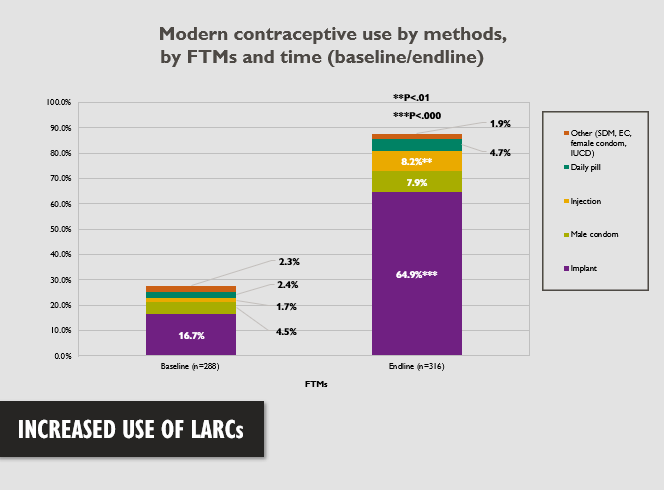

Dr. Femi-Pius: In CRS, overall use of modern contraceptive methods by FTMs increased from 26% to 79%. We saw increased use across a range of methods, most strikingly with the implant (from 17% to 65%), reflecting their intentions to wait 3 or more years before having their next child.

Mr. Osseni: In Niger, among married adolescent girls interviewed at endline, 97% reported ever having used a modern contraceptive method—with 48% having used injectables, 33% pills, 15% implants, and 1% IUD and LAM, respectively; this aligns with method mix among new users at affiliated health facilities.

At what percentage of FTPs used implants and IUDs as opposed to other modern FP methods?

Mr. Osseni: In Niger, married adolescent girls interviewed at the final survey had ever used the following methods: injectables (47% ), pills (33%), implants (15%), IUDs (1%) and LAM (1%).

Dr. Shaw: In the DRC among 39.9% of sample that are current users of modern contraception, FTP at endline reported that they were currently using: male condoms (48.8%), OC (21.4%), FAM (16.3%), implants (12.1%), injectables (6.1%), IUD (1.0%).

Dr. Femi-Pius: In Nigeria, the majority of FTM contraceptive users were choosing a LARC method - specifically the implant. Method choice by FTMs using a modern contraceptive at endline were: implants (65%), male condoms (7.9%),injectables (8.2%), OCs (4.7%), and all other methods (1.9%),

In Nigeria, you reported a high use of implants at endline. Could you share reflections on that? Were you concerned about method skew given the use of implants (>60%)?

Dr. Femi-Pius: We were a bit surprised at the level of interest in LARCs, but this was very much in line with the spacing intentions of the FTMs and their partners. Our endline data showed that the majority of FTPs wanted to wait three or more years before having their next child, which helps explain their interest in LARCs. Also, access to LARCs had also increased through the implementation of Cross River State’s Task-Shifting/Task-Sharing policy of provision of LARCS (Implants) by CHEWs. So many FTMs/FTPs were able to obtain the method that met their reproductive needs and intentions.

Are there any issues/policies for accessing FP methods in the DRC or Niger (e.g. mother’s age, number of children, marital status)?

Dr. Shaw: We are unaware of any restrictions on access to FP in national policy. But there are likely other access-related issues for women to obtain contraception.

Mr. Osseni: In Niger, there are no restrictions on access to FP in our national FP policies.

Challenges and Surprises

Was there a reason for low interest among young mothers in early pregnancy in Niger?

Mr. Osseni: Due to certain social considerations, especially primiparous married adolescents do not want to reveal pregnancy in the first trimester. This made it difficult to identify them in the community. That is why we targeted all newly married women without children (pregnant or not) at the start of the intervention.

When you compare your experience working with FTPs vs. other target youth populations (like general adolescents/youth, or newly married, youth in school, etc.), do you see any particular opportunities or challenges?

Dr. Femi-Pius: I think we are seeing an important opportunity with FTPs. They are going through such a period of transition and need support in so many areas—not just health. Our experience working with them suggests that these young women and their partners are open to solutions that can help them and want access to health information and services. One challenge, though, is that they generally have no prior connection to the health system. So having community-based networks that can identify and connect these young people to the services they need is critical.

Mr. Osseni: In our rural context in Niger, it is very difficult to target unmarried adolescent girls (whether in the general population or in school settings) with reproductive health interventions. Attitudes have not changed much in this regard because people still believe that RH/PF interventions targeting unmarried adolescent girls encourage them to engage in sex before marriage. But the government with the support of its partners is working to change things, especially in schools, by introducing reproductive health education for adolescents and young people into the training curricula for students.

Were there any unintended consequences that arose from these programs? If so, how were they monitored and/or mitigated?

Dr. Shaw: In the DRC, we saw significant increases in perceptions of intimate partner violence as typical behavior and as approved behavior in their communities’ intervention congregations, which was unexpected. We hypothesize that it is possible that it is awareness of what IPV is that is increasing more so than social norms are “worsening.” We are working more on understanding this finding in order to monitor/mitigate it in future.

Mr. Osseni: In Niger, one of the unintended consequences revealed by the final survey was an increase in the number of men who responded affirmatively to the question of whether women should tolerate intimate partner violence to maintain the status of their households—from 3% at baseline to 53% at endline. However, since the project addressed issues of gender-based violence, we linked this increase either to a lack of knowledge of the definition of violence in the baseline survey or to the effect of income-generating activities that empowered the adolescent girls benefiting from the program. These findings are informing how we plan, implement and evaluate such interventions going forward.

Dr. Femi-Pius: We did not see any obvious unintended consequences arise during our project, but it is interesting to hear how issues of IPV and GBV arose in both Niger and DRC. Feedback from both FTMs and their partners in our project indicates that they, too, were dealing with conflict and were looking for skills/tools to manage and improve their relationships. While we addressed this in our interventions—and these were among their favorite topics—what we’re learning across FTP projects suggests that we need to do more.

What were some other key challenges?

Dr. Femi-Pius: In Nigeria, we were fortunate to build on an existing MNCH/FPs, so service delivery capacity and community networks were largely in place. We did face some initial challenges in recruiting men to join the small groups, but we found once we got them there, they stayed and participated well.

Mr. Osseni: In Niger, identified challenges included:

- Mobility of health workers trained in the provision of youth-friendly services

- Demand for long-term methods at the health post level (only available at the integrated health center)

- Seasonal migration of husbands limiting their time of exposure to messages

- Request for income-generating activities for FTPs

Dr. Shaw: In the DRC, these mostly revolved around retaining the population as they attended different congregations throughout the program, engaging men in intensive couple dialogue sessions, and the backdrop of political and economic instability, that interrupted the delivery of the intervention.

Sustainability

What processes did the project engage in to develop sustainability plans for their interventions? Which stakeholders were engaged? How did this engagement happen? How do national governments plan to fund sustainability and institutionalization?

Dr. Femi-Pius: In Nigeria, the FTM project was part of a larger initiative, Saving Mothers, Giving Life (SMGL), through which we had an on-going consultative process with the state Ministry of Health and the Primary Health Care Development Agency. So FTP activities and results were integrated into this process, which included working with government partners to look at how these different initiatives would be sustained and scaled up across the state. At a more local level, we worked with community leaders and the CBO partner to include FTP efforts within community health planning processes.

Mr. Osseni: In Niger, we involved the actors of the Ministry of Health from the beginning of the intervention. They were given responsibility for identifying and strengthening the capacities and monitoring of community actors, allowing us to establish a relationship of accountability between them. Each community actor belonged to the local Integrated Health Centre (CSI) and was fully involved in the activities of the CSI. A plan for the sustainability of the interventions was developed with the local MoH actors and the activities that could continue under the leadership of the MoH were selected. At the end of the project, all the project equipment and tools were entrusted to the MoH to enable the intervention to continue. Finally, in its annual work plans, the MoH programmed activities to ensure the sustainability of the intervention.

Dr. Shaw: We engaged a large, national network of Protestant faith leaders (Eglise du Christ du Congo—ECC) very early and throughout the intervention with participatory involvement in development of the intervention. We set up the research such that scale-up would immediately occur in comparison congregations, post-endline. The ECC has been very supportive and interested in scaling this up to other Protestant congregations throughout the country.

ABOUT THE EXPERTS

Oluwayemisi Femi-Pius, MD, Senior Technical Manager, Pathfinder International Nigeria. Dr Femi-Pius has over 16 years of experience in clinical practice and in designing, implementing, and managing maternal and newborn health, family planning, HIV and AIDS, and tuberculosis programming in resource-constrained settings.

Akim Assani Osseni, MPH, Reaching Married Adolescents Project Technical Manager and Acting Community-Based Service Manager, Pathfinder International Niger. Mr. Osseni is an epidemiologist, biostatistician, and expert in intervention epidemiology with over five years of implementation experience with adolescent and youth reproductive health projects.

Bryan Shaw, PhD, Senior Research Manager at the Georgetown University Institute for Reproductive Health. Dr. Shaw currently provides research support for the USAID-funded Passages studies conducted in Burundi, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Senegal, Niger, and Nigeria.